Revelation: The Original Graphic Novel? - Week 3

When my son became a teenager, it became more difficult to inspire him to read a book. This had never been a problem before. We were stuck and unsure until I came across a graphic novel version of Frankenstein at the local library, and his enthusiasm returned. In his adolescent world, the vivid pictures and rich story reached him like nothing else had.

John must have known the same thing as he painted the vivid word pictures of Revelation for his community. The visions would be well suited for a graphic novel. Pictures can communicate great truth, sometimes reaching and impacting an audience, especially an oppressed one, in a way that more cerebral words cannot.

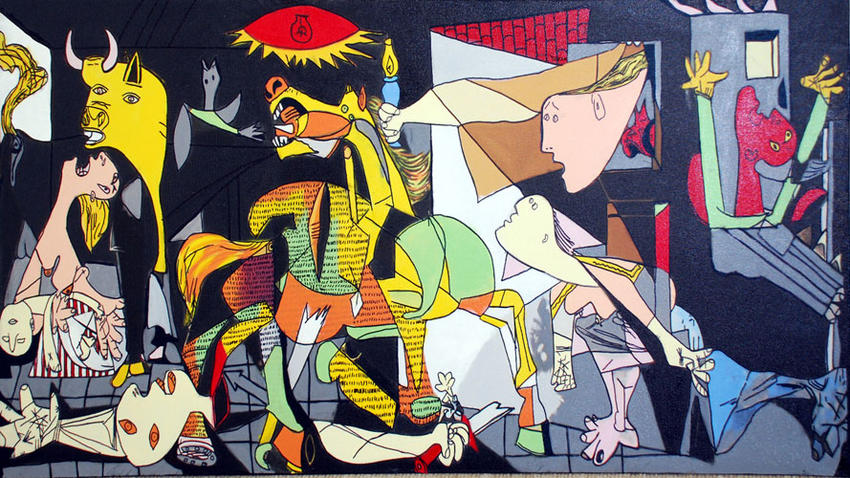

(See Guernica on Wikipedia)

Vernard Eller, in his book The Most Revealing Book in the Bible, compares the book of Revelation to Picasso’s famous painting, Guernica, 1937 (shown above). Known as one of the most moving and powerful anti-war paintings in history, Picasso had painted it in reaction to the Nazis' bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Painted in black, grey and white, it is full of symbols which convey the intense suffering of war. The images are timeless and universal. Both animals and people are affected — bulls and horses, a mother with a dead child, a dead soldier, an imploring man.

You won’t recognize any telltale details from Guernica like you would in a photo, such as street names or people’s identities, but to look for factual truth would be to miss the point. The details are exaggerated and full of discord. They work together to create an impact that an undistorted snapshot never could. Anyone who had experienced the bombing in 1937 would have agreed that the painting expressed not factual accuracy but what some call “meaning truth”. And this is the truth that still grabs us in Picasso’s painting all these years later.

In all times and places, war has inflicted trauma on so many, even for generations after the war is technically over. And of course, there are many kinds of wars, not just those between countries. Addictions, relational discord, physical or mental illness, poverty, loss, hunger, loneliness — Picasso’s images grab our hearts, reminding us of evil’s dark fruit, the terrible disruption of existence itself.

John too needed to express the horror of the times at hand, but he had an even greater task as he sat down to record the visions of Revelation, describing not just one event but the total enormity of world evil. There is another significant difference between Picasso and John. As we’ll see in upcoming blogposts, the dark images in Revelation are answered by the image of a slaughter-marked lamb. Nothing else will right evil’s tendency to get worse.

The Audience of Revelation

Who can forget the photo of 3-year old Aylan Kurdi in 2015? Found washed ashore after his family was fleeing war in Syria, his heart-breaking death became a world wide wake-up call to the refugee crisis.

Picasso’s painting had the same effect in 1937, not just on the citizens of Guernica, but around the world. It caught the world’s attention when it went on a brief world wide tour, telling the news of the Spanish Civil War like no other media reports had.

Both situations had alarming pictures which disturbed our comfort, but a context of intense suffering was behind it. Those in suffering were no doubt saying, “Thank God someone is hearing about our plight. Maybe now something will change.”

The disturbing images of Revelation reflected some desperate times as well. Hearing John’s visions in the first century, the early Christians would have understood immediately, just as those in the town of Guernica understood Picasso’s painting. Just who were these people and what were they going through?

The Persecuted

Some early Christians, including the author of Revelation, experienced persecution and open hostility from Rome because of their faith. In the most extreme cases, allegiance with God in Christ meant torture and death. Even the writer John was an imprisoned on the island of Patmos as the authorities figured out that his message was subversive. John was highly critical of the status quo and a sharp advocate for change.

Many people didn't know what to make of the Christians. They worshipped only one God, and put their faith in a crucified, risen God. To say that Jesus (not Caesar) was Lord meant Jesus was the Messiah, King and Risen One. This gave Christians a higher form of loyalty than Rome’s rulers and it made people nervous.

It meant they didn’t fit in with the local Jews either. Persecution was not a systematic campaign, imposed from the top down. It was local and sporadic. It started when local people grew uneasy about the presence of Christians.

A word about Revelation’s language — When people are oppressed, the only language that makes sense are the shocking words of a revolutionary. Koester points out that unlike the rest of the New Testament, the original Greek in Revelation confounds translators as it breaks all grammar rules.

Like rappers who stand outside of culture by using incorrect grammar and colloquial expressions, the language of Revelation is non-conformist and defiant. Just as a wise mentor knows exactly what to say and how to say it, no matter the situation, John chose his words well. Knowing his audience was oppressed, John used bad Greek to make a point, choosing a counter-cultural form of speech for his counter-cultural message. Like the distorted images of Guernica, John’s language was subversive, similar to the black people who cried, “I ain’t gonna take this no more!” People in suffering listen to “voices from the margins," and John understood his role as a prophet. His street language would have reached the oppressed.

The Assimilated

While some Christians faced open hostility, others simply felt a more subtle pressure to conform. Life in an inter-religious world gave them some sticky dilemmas. Should they eat food sacrificed to idols? Should they go to festivals dedicated to local gods like Dionysus or Artemis to preserve friendships or business contacts? Their faith set them apart. How were they to stay true to their convictions while getting along socially with neighbors who didn’t share their faith? How far could they blend into their surroundings before they lost their identity?

A modern parallel might be seen in China today. While China has recently changed to a 2-child policy, stories of the pressures to conform in the old days are prevalent. Those who did not conform to the 1-child policy were penalized with social shunning, docked wages or even termination, hefty fines, forced abortions and even the euthanizing of female babies.

Rome had its own seductive propaganda. Christians were manipulated and wooed into the worship of empire, and following a different way meant paying the price if you didn’t conform. The visions of Revelation challenged the myth of Rome. The Jesus movement was a home for people who were disoriented by Rome’s manipulation. It could be expensive, restrictive and oppressive to follow Christ.

Assimilation happens to us when we are under the illusion of “the way things are," blithely not thinking about things. Author Walter Bruggemann calls this the illusion of empire. The dominant culture puts us to sleep so soundly that we don’t even know when something is wrong. We think if we’re loyal to the empire, then somehow we’re secure, but when things are at their worst, the cracks start showing. Selling out leads to deadening pain and the need for change appears. So it’s a wake up call for us.

The Complacent

It doesn’t take much imagination to see ourselves as complacent. Even if we are seduced into thinking that all is right with the world as long as all is right in our world, there’s a deeper truth if we open our eyes. There is a battle going on in the world and in our souls. We are always more poor than we realize.

We are never just “one” of Koester’s 3 stages (persecuted, assimilated or comfortable). Perhaps you can see yourself in any of these 3 situations. For those who feel threatened, Revelation is a book of encouragement to keep the faith amid open hostility. It encourages us to know that truth will prevail. For those who are just trying to assimilate and get along with their neighbors, the vision of Revelation may act as a challenge as John makes a sharp and emphatic contrast between God and those things that take God’s place. For the comfortable, the message may be disturbing and challenging. Revelation calls them to open their eyes.

Whether it’s an oppressive regime like Rome, the bombings in Guernica, a refugee crisis, or deadening comfort, trauma calls out different responses in us all. Revelation’s message is as universal as Picasso’s, and more hopeful.

Koester puts it in a nutshell, “The struggling are called to persevere and have the same patient endurance that Jesus had, the complacent are to become recommitted, and the assimilated are called to a renewed sense of integrity in a complicated world.”

Questions for Engagement — Week 3

- Is there a picture or graphic image that ever spoke to you more than words could at the time?

- What similarities can you see between the 1st century and our 21st century worlds?

- Persecution — What personal or cultural struggles are requiring perseverance and endurance from you?

- Assimilation — What are the challenges of opening yourself to the faith of another person out of respect to them, while still honoring and standing true to your own faith? What does it mean to stand in your own story?

- Complacency — Have you ever been challenged to move in a different direction, out of your comfort zone? What motivated you to change?

In case you’d like to read more…

- The Most Revealing Book of the Bible: Making Sense out of Revelation by Vernard Eller, specifically the chapter called “An Excursus on Trauma” — available free online.

- Craig Koester, The Apocalypse: Controversies and Meaning in Western History, Lecture 4 — “Origins of the book of Revelation”

- Pastor Greg Boyd from Minneapolis has a 40 minute sermon called “A Vision of Beauty.” In it, he introduces the book of Revelation, giving three things to keep in mind when reading it. He also compares Picasso’s painting of Guernica to Revelation.

Next Post